Legally Mandated Abortion Info is Often Inaccurate

By OBOS — April 11, 2016

This blog was originally posted in the Women’s Health Policy Report, published by the National Partnership for Women & Families, www.nationalpartnership.org/report.

Summary of “Informed or misinformed? Abortion policy in the United States,” Daniels et al., Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, Jan. 5, 2016.

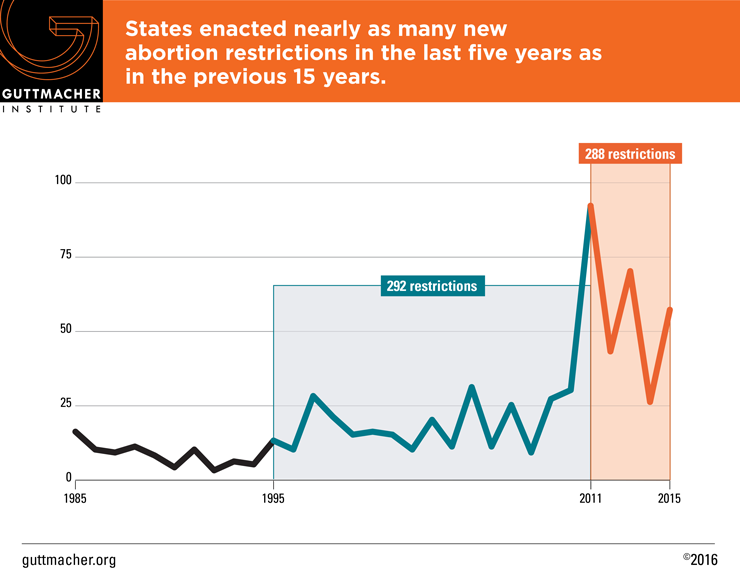

There has been “a dramatic expansion of state-based restrictions on abortion” since 2010, particularly among “informed consent statutes, which require that a woman seeking an abortion receive a state-authored informational packet before the abortion procedure,” according to Cynthia Daniels, a professor of political science and women’s and gender studies at Rutgers University, and colleagues.

According to the researchers, informed consent laws “typically require details of fetal development and information about the alternatives to abortions and risks associated with abortion and pregnancy.” The laws have a potentially large affect: “66 percent of all women seeking abortions live in informed consent states,” the researchers write. Noting the lack of research on the accuracy of informed consent materials, the researchers wrote that they conducted a “comprehensive study of state informed consent materials, with a particular focus on information regarding embryological and fetal development.”

Legal background

The researchers explained that the Supreme Court in Planned Parenthood v. Casey “affirmed three principles central to the constitutionality of informed consent laws: that the state has an interest in fetal life from the moment of conception, that the state could prefer childbirth over abortion, and that the state could enact regulations to ensure that a woman’s choice was ‘thoughtful and informed.'”

According to the researchers, while the Casey ruling permitted the state to promote fetal life, and to be biased in favor of childbirth, it held that the informed consent materials “must be ‘realistic’ and [convey] ‘accurate scientific information.'” As long as the information “is truthful and not misleading,” the high court stated, informed consent requirements “violated neither the woman’s constitutional right to choice nor the woman’s right to medical privacy,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers stated that the ruling “opened the door to the widespread passage of informed consent laws in the states,” with 37 states implementing such laws by 2013. Of those states, 29 “specified that mandated scripts be delivered to any woman seeking an abortion.”

The majority of states “followed the same general format in their mandates, including a list of alternatives to abortion …, the medical risks of abortion and childbirth” and “the bulk of the information …. focused on embryological and fetal development.”

Methods

For the study, the researchers “collected informed consent materials from the twenty-three states that had produced such materials and had made these materials publicly available.”

According to the researchers, states usually required that print and online versions of the materials “include visual depictions and verbal descriptions of the [fetus] at two-week increments.” Some states also required that fetal development information “include statements regarding the functionality of certain physical structures at various gestational ages, such as heart, brain, or lung development, or in the ability of a fetus to feel or experience pain,” the researchers wrote. State health departments authored all of the materials examined.

The researchers collected the informed consent materials in spring 2013 and “extracted all statements regarding embryological and fetal development.” After eliminating duplicate information and combining statements that were factually similar, the researchers “aggregated 896 statements about fetal development” into a survey. The researchers, focusing on the medical statements themselves, excluded from the survey geographical data and “all photos, drawings, and images.”

The statements were categorized by two-week development periods and standardized by age since the woman’s last menstrual period (LMP), the researchers wrote, adding that the information was further categorized by “body part or function.” The researchers then created two five-point scales based on the Casey standards that the information must be “‘truthful and ‘nonmisleading.'”

The researchers distributed the surveys to “seven specialists in embryological and fetal anatomy,” who were asked to rate the information on the “‘truthfulness-falsity’ scale” and the “nonmisleading-misleading” scale. Three of the specialists “reviewed statements on early pregnancy and four evaluated statements on late pregnancy.” According to the researchers, statements considered medically accurate had to be both “scientifically correct (in terms of biological development) AND … nonmisleading (meaning that it gives a ‘correct impression’) to a patient seeking reproductive medical services.”

Results

One-third of statements were ‘medically inaccurate’

The researchers found that 69 percent of the statements were ranked as medically accurate and 31 percent were ranked as medically inaccurate. Overall, according to the researchers, “29 percent of all responses received a rating of ‘don’t know/unsure.'” While those responses were eliminated from the analysis, the researchers noted that information regarding fetal development in the first and second trimesters was more likely to be rated as unsure. Further, many statements ranked as unsure “pertained to traits not typically addressed in embryological medical texts, such as the ‘activities’ of the fetus” or “to traits that vary widely between pregnancies.”

The researchers also found that “inaccuracies ranged from about 15 percent to 46 percent across states.” Overall, North Carolina had “the highest level of inaccuracies” with 46 percent, or 36 of its 78 statements, being rated as medically inaccurate, while Alaska “had the lowest level of inaccuracy, with 15 of its 102 statements (or 15 percent) rated as inaccurate.”

The researchers also found a “small, though not significant, association between region and levels of inaccuracy.” Overall, “[h]igher levels of inaccuracy were found in the South and Midwest, specifically the south Atlantic (23 percent), west south central (29 percent), and east north central (39 percent),” the researchers wrote.

Medically inaccurate statements disproportionately found in first trimester

According to the researchers, “45 percent of statements about the first trimester were rated as medically inaccurate … compared to 29 percent in the second trimester … and 13 percent in the third trimester.” They wrote that the findings show “a pattern of proportionally decreasing percentages of medical inaccuracy as pregnancy progresses.”

The researchers found that medically inaccurate statements were disproportionately concentrated in the two to six weeks since a woman’s LMP. According to the researchers, “over 50 percent of statements in week 2 [were] found to be inaccurate,” as were more than 30 percent of statements in week four since a woman’s LMP and 38 percent of statements in week six since a woman’s LMP. They added that the rate of medical inaccuracy “increased between weeks 8 and 16 and rose to over 20 percent in week 26.”

Overall, the researchers noted that only “a small number, 169 (9 percent), were rated unanimously as both true and nonmisleading” by all of the experts reviewing those statements. According to the researchers, such statements “were concentrated more heavily in the third trimester.”

Medically inaccurate statements disproportionately concentrated on particular body parts, systems and functions

The researchers said reviewers “found particular patterns of inaccuracies: fetal development was ‘accelerated’ by misrepresenting development of certain body systems earlier than in developmental reality.” Further, the reviewers found that “body systems that appear to attribute human ‘intentionality’ or more ‘baby-like’ characteristics to the embryo or fetus … were more likely to be misrepresented at earlier stages of development.”

According to the researchers, “Medical inaccuracies were grouped around statements about certain body systems, particularly extremities, internal development, and size and weight, as well as statements about viability and activity.” Specifically, the researchers noted medically inaccurate statements accounted for:

- 29.94 percent of statements about extremities;

- 26.13 percent of statements about internal development;

- 26.89 percent of statements about size and weight, often to make the fetus seem larger or heavier than is medically accurate;

- 23.15 percent of statements about fetal movement or activity, some of which were inaccurately ascribed to fetal intention; and

- 20.53 percent of statements about fetal viability.

Implications

The researchers wrote that while providing women with detailed information about fetal development does not directly violate the Casey ruling, such materials “cannot use medically inaccurate information in the service of persuasion.” That “would be a clear violation of the principle established by Casey,” the researchers wrote.

According to the researchers, “The fact that medically inaccurate information is systematically inaccurate in the direction of exaggerating the ‘baby-like’ capacities of the embryo/fetus suggests that the state is presenting misinformation about embryological/fetal development in the interest of persuading women to choose birth over abortion.”

In addition, the researchers noted that “the level of medical inaccuracy in the information provided to women in informed consent states suggest that, in practice, informed consent laws fail to achieve the purported state interest in ensuring that a woman’s choice is ‘thoughtful and informed.'” According to the researchers, the medical inaccuracy of the statements also would not withstand the standard established in the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling in Planned Parenthood v. Rounds, which held that states have “‘wide discretion to pass legislation in areas where there is medical and scientific uncertainty.'” Noting that “most aspects of human development are well established,” the researchers wrote, “While there may be areas of dispute, medical information provided by the state should be based on medical consensus, and in the absence of consensus such information should not be presented as fact.”

Conclusion

The researchers noted that part of the Casey ruling held that providers do not have to comply with informed consent requirements if in their reasonable medical judgment they believe that conveying the mandated information would have a “severely adverse” effect on the patient.

According to the researchers, “The provision of inaccurate medical information to a patient for any medical procedure would no doubt have an adverse effect on that patient,” so “it is deeply problematic for the state to mandate that physicians provide” such misinformation, particularly for abortion care. They wrote, “Violating the confidence of a patient to receive accurate information from [medical professionals] not only might have ‘severely adverse’ effects on patients but also potentially undermines confidence in the integrity of the health care regulatory and medical provider systems.”

The researchers explained that while challenges to informed consent laws have not succeeded in federal courts, the court rulings “have been based on assumptions of the medical accuracy of the information provided to women.” Noting that their study debunks that assumption, the researchers wrote, “[T]he level of medical inaccuracies evidenced in this study calls for a rethinking of the soundness of the court’s logic in upholding abortion-related informed consent laws.”